Object Relations Therapy: Overview

Background

There is a relatively wide range of psychoanalytic approaches:

Orthodox Freudians

Object Relations (OR) Theorist (most reject drive theory, except Klein)

Ego Psychologist

Interpersonal Theorists

Intersubjectivisits

Note: There is some controversy about whether the psychoanalytic schools of thought can be delineated as clearly as is done here. For example, some consider Kohut an Object Relations (OR) theorist. Though, Kohut is a post-object relations figure. His work has been coined “self psychology”; and is considered an offshoot or advancement of object relations. In his work, the prominence of how narcissism develops, flows, and forms the self is emphasized.

On Motivation: There is some disagreement here. It has been said that variants of psychoanalysis might be characterized according to the degree to which they accept or reject drive theory (i.e., Eros/Thanatos, Life/Death, Sexual/Ego) as motivating forces.

Where they generally agree:

The primary focus is on the mother-child dyad. She is the most important as she has the breast, the source of sustenance for the baby. The breast is the first good object.

The unconscious is a powerful, influential force; for drive theorists, the unconscious contains our sexual and aggressive impulses. For relational theorists, the unconscious contains “objects” of the self and others.

On Human Nature. M. Klein, presents what seems to be a rather negative view of human nature, though she acknowledges libidinal energy (a pathway of coming to a state of love). Early developmental states are scary for the infant (feelings of aggression, and shifting emotional states).

Object Relations

Perhaps the most spectacular OR theorist was Melanie Klein. She is also often credited with being the founder of the Object relations approach. Klein was considered a heretic at the time by the psychoanalytic establishment. Note: unlike other OR theorists, she accepted drive theory (DT). M. Klein observed (or theorized):

● Harsh & Punitive superego emerged from the relationship between child & mother (not from the Oedipus complex).

● In order to make progress, the therapist must interpret the negative transference and bring it to the forefront.

Other important OR theorists include R. D. Fairbairn and D. Winnicott.

Winnicott on DT: drives are directed at objects (not simply expressing drive or the other, and not simply object seeking or release).

As the object-seeking process begins in very early in life, the focus is often on early development (pre-Oedipal) stages and the mother-child dyad/relationship.

Central Constructs

Object

The term object was first used to refer to people and things in the environment. However, object is now most importantly referred to as internal representations of psychological structures formed early in life via the internalization of interactions w/ important others. The first object is the breast.

Internalized objects become part of the developing child’s self, and the quality of the child’s relationships with them– and particularly the attachment to them–determine the functioning of the individual. (Murdock, 2016, p. 83)

The object, according to Kernberg, is composed of an image of the self, an image of the person, and associated emotions.

Projection

Projection (as well as introjection and splitting) is first a way of relating to the breast and the primitive emotions associated with it. Later, projection can generalize to other objects (e.g., people).

The happy infant, one who is sustained and nurtured by a breast, projects positive feelings and emotions on the breast– the breast becoming a “good breast.” The angry, hungry infant associates those feelings with “bad breast.” These early object relations are then transferred (or generalized/projected) onto other important persons.

Introjection

Taking aspects in. Infants internalize, or swallow whole, into their unconscious psyche, categories or representations of reality. These are known as “introjects” or “objects.”

Splitting

A normal process. All infants go through it. Dangerous feelings, objects, and impulses are separated from pleasant ones. It is a defense process.

… the infant has strong contradictory feelings (such as love or hate, pleasure or frustration) but can only keep one of these feelings or thoughts in its immature awareness at a time. The result is a representation of a part object, which is an object with only one particular quality, such as “frustrating”; the seemingly contradictory quality of “pleasure giving” is excluded from the infant’s awareness. Only with growing maturity will the infant be able to integrate simultaneously into one stable image the seemingly opposite aspects of the same object or experience, such as the frustrating aspects of the pleasure-giving mother. To maintain this fragile personality structure, the infant uses splitting to keep apart the conflicting feelings that the good and bad aspects of the mother arouse internally within the infant. (St. Claire, 1996)

Projective Identification

Hamilton (1988) writes “Lovers describe themselves as giving their love. They give their selves and hearts to each other. These common expressions of love are examples of projective identification– imaging a loving aspect of oneself to be actually inside the other people, and acting accordingly” (p. 96).

Projective identification is perhaps one of the biggest contributions of M. Klein, which cemented her place in the history of psychology. Projective identification is a process that begins when the infant projects some scary feelings outward onto another object (such as the breast or mother).

Case Illustration

Imagine a client with extreme health anxiety (i.e., hypochondria). The client had an early history of great conflict and injury. The client is the eldest child and their mother didn’t take care of them or their younger siblings. Client’s mother is currently in a nursing home and in poor health. They formed an entire identity around the early conflict and injury (cf: a victim identity). It makes sense for them to be sick in some way. It may also help them get attention. They took on the role of caretaker, and that continues as they are left to take care of their mother alone. They are so wrapped into their mother’s care, even though contact with their mother is extremely distressing and unpleasant for them.

This is a primitive projection in which the client identifies completely with their mother’s desperation at not being able to get the attention, and care, from their caretakers. The involvement with their mother’s health is ultimately a projective identification, not genuine empathy or concern. The client actually believes they would be better off if their mother died.

[Projection] helps the ego to overcome anxiety by ridding it of danger and badness. Introjection of the good object is also used by the ego as a defense against anxiety. . . .The processes of splitting off parts of the self and projecting them into objects are thus of vital importance for normal development as well as for abnormal object-relation. The effect of introjection on object relations is equally important. The introjection of the good object, first of all the mother’s breast, is a precondition for normal development . . . It comes to form a focal point in the ego and makes for cohesiveness of the ego. . . . Much of the hatred against parts of the self is now directed towards the mother. This leads to a particular form of identification which establishes the prototype of an aggressive object-relation. I suggest for these processes the term ‘projective identification’. (Klein, 1946/1996, pp. 6-9)

Theory of the Person & Development of the Individual

The self, inherent and present at birth, develops through interaction w/ others, “building psychic structure by internalizing objects” (Murdock, 2016, p. 85). In the right environment, the infant develops the capacity to resolve splitting (dichotomous “good/bad,” “happy/sad,”) and integrate various internal objects into wholes.

The infant is beset with turmoil. Death instinct threatens annihilation (remember drive theory); there are feelings of persecution. At the same time, the mother provides care (feeding), resulting in the internalization and idealization of the good object (i.e., the good breast). The death instinct and feelings of persecution are projected onto the bad breast. These intense emotions are difficult to deal with. The infant shifts from love to hate and aggression. These feelings are later generalized to the mother and then the father.

Winnicot coined the term good enough mother, a mother who mostly meets the infant’s needs. She creates a safe holding environment. This safe environment, as well as quiet time, is necessary for the baby for ego development.

Winnicot also coined the term transitional object, which is something innate like a teddy bear or blanket. Winnicot (1971) writes,

It is not the object, of course, that is transitional. The object represents the infant’s transition from a state of being merged with the mother to a state of being the relation to the mother as something outside and separate. (p. 14)

Or in the words of Greenberg and Mitchell (1982), these entities provide “a developmental way station between hallucinatory omnipotence and the recognition of objective reality” (p. 195).

HEALTH AND DYSFUNCTION

Healthy people have good object relations, a coherent sense of self, and inner drives do not significantly distort current relations. Internalized objects are not split into “good” and “bad” objects but integrated into a whole. The ego develops as it’s own distinct object and can recognize the primary good object as separate from one’s own self.

Dysfunction is the result of faulty early development or bad mothering.

NATURE OF THERAPY

Assessment

OR therapists are not really interested in formal assessments. They are more likely to observe the client’s behaviors as clues to understand the underlying dynamic processes.

Overview of the Therapeutic Atmosphere & Roles of Client & Counselor

Looks a lot like Freudians, but OR therapists are more likely to take into consideration the environment of therapy. Essentially, therapy replicates the early relationship with the caregiver.

Klein differed from others in some aspects. She:

Advocated for early use of deep interpretations

Emphasized early phases of experience (pre-Oedipal)

Much more interested in the aggressive impulses of the client.

Goals

Good therapy should restore healthy object relations, and consequently, a solid sense of self.

For Winnicot: the development of the self.

For Fairbairn: developing new ways of relating to others.

For Kernberg: integration of the part-objects within the self and the resulting abilities to maintain a continuous sense of self- and others, empathize w/ them, and reflect on one’s own experiences.

Process of Therapy

OR therapy is insight oriented.

They are also very interested in the phenomena of transference (see Kant’s Dove). As Murdock (2016) points out, Fairbairn thought the client will eventually experience the therapist as “the old, bad object” from earlier relationships.

Countertransference is no longer seen as an obstacle to analysis, it is a tool to understand the client. As Carotenuto wrote (1986), it represents a kind of “Kant’s Dove” for the analytic enterprise. The dove fights against the wind (transference & counter-transference) and wishes it weren’t there so they could fly more freely, however without the air and wind, the dove cannot fly at all.

Therapeutic Techniques

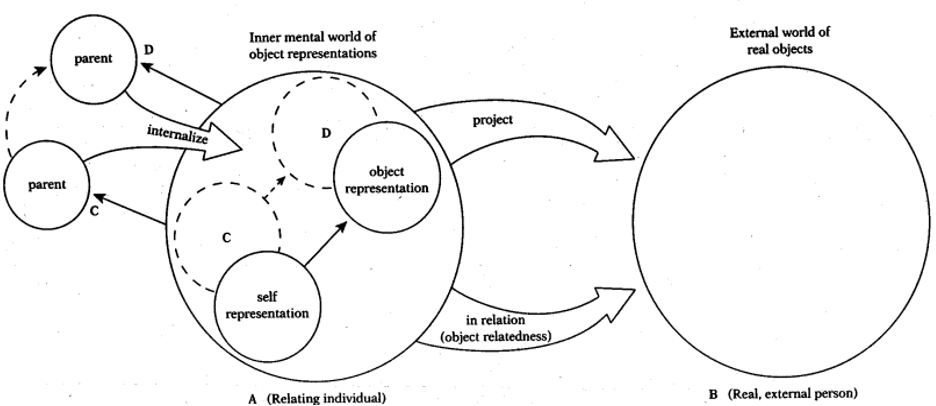

OR is heavily transference-focused. In fact, the relationship between therapist and client is believed by many OR theorists to be the curative factor. OR may be viewed as a “three-person” model of therapy according to Kernberg (2004):

This three-person model stresses the double function of the analyst as being immersed, on the one hand, in a transference-countertransference relationship and, on the other, as maintaining an objective distance from which observing and interpreting the patient’s enactments of internal object relationships can be carried out. (p. 298)

Return to the OR Model Image presented at the beginning of these notes. Is it clear where the “third” position Kernberg discussed, fits in?

OUTCOME AND THEORY-TESTING RESEARCH

It should be noted that American psychoanalysts have traditionally been dismissive toward outcome research (Shedler, 2010). It would be a mistake to reject psychodynamic therapies for their tendency to avoid systematic research. Rather, we ought to look at the research before we can reject it, right? Perhaps surprising to some, it appears the research supports psychodynamic and more contemporary cognitive-behavioral modalities. One can make sense of this in light of the contextual model (see Wampold, 2001; Imel & Wampold, 2015) as both modalities contain common factors predictive of outcome (e.g., the real relationship and expectations). In regards to research specific to object relations, there is a relative dearth of information. Perhaps this is because much research is conducted by advocates of a specific approach and proponents of object relations theory may generally be dismissive of research-- resulting in less of it. Nonetheless, I have provided short summaries of some of the extant research (see below).

Outcome Research

Clarkin and colleagues (2001), examined the effectiveness of Transference Focused Psychotherapy (TFP) for clients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) using a simple pre-post comparison design with clients who had received 1 year of outpatient treatment (N = 23). This study is relevant as TFP is based on object relations theory. It was found that compared to the year prior to treatment, the number of suicide attempts by patients significantly decreased. In addition, the number of hospitalizations and days of psychiatric hospitalization significantly decreased.

Doering and colleagues (2010), in another TFP study examining the treatment of female clients with BPD, compared TFP to treatment provided by community psychotherapists. This study was a randomized controlled trial (N = 104) and clients were treated for 1 year. Transference-focused therapy was found to be superior in the domains of borderline symptomatology, psychosocial functioning, personality organization, and psychiatric in-patient admissions. In addition FTP had significant fewer dropouts compared to treatment provided by community psychotherapists (39% v. 67%). Both groups had improved significantly on scores of depression and anxiety.

Shakiba and colleagues (2011) conducted a single-subject experimental design testing the efficacy of Brief Object Relations Psychotherapy (15 treatment sessions) for women suffering from major depressive disorder comorbid with “cluster C” personality disorders using outcome measures for perceived quality of life and depression. Six participants were randomly assigned to an AB design with follow-up. The treatment was found to be statistically significant with measures of perceived quality of life reaching the normal range and depression levels went from moderate-to-severe to minimal-to-mild ranges.

Theory Testing Research

Van and colleagues (2008) in an exploratory study (N = 81) examined object relational functioning (ORF) for the therapeutic alliance and outcome in short-term psychodynamic supportive psychotherapy in clients with mild to moderately severe depression. The Developmental Profile (Abraham et al., 2001) was used to determine one’s ORF score. The study found ORF to be relevant for depression and distinctive from therapeutic alliances.

Largely adapted from Murdock, 2017.

-

Horner, A. J. (1991). Psychoanalytic object relations therapy. Jason Aronson, Inc.

Scharff, J. S. (2001). Case presentation: The object relations approach. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 21(4), 469-482.

Widzer, M. E. (1977). The comic-book superhero: A study of the family romance fantasy. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 32, 565-603.

-

Abraham, R. E., Van, H. L., van Foeken, I., Ingenhoven, J. M., Tremonti, W., . . . Spinhoven, P. (2001). The development profile. Journal of Personality Disorders, 15(5), 457.

Carotenuto, A. (1991). Kant’s Dove: The History of Transference in Psychoanalysis (J. Tambureno, trans). Chiron Publications.

Clarkin, J. F., Foelsch, P. A., & Levy, K. N. (2001). The development of psychodynamic treatment for patients with borderline personality disorder: A preliminary study of behavioral change. Journal of Personality Disorders, 15(6), 487.

Doering, S., Hörz, S., Rentrop, M., Fischer-Kern, M., Schuster, P., Benecke, C., ... & Buchheim, P. (2010). Transference-focused psychotherapy v. treatment by community psychotherapists for borderline personality disorder: randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 196(5), 389-395.

Kernberg, O. (2004). Contemporary controversies in psychoanalytic theory, techniques, and their applications. Yale University Press.

Klein, M. (1996). Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 5(2), 160-179.

Hamilton, N. G. (1988). Self and others: Object relations theory in practice. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Murdock, N. L. (2017). Theories of counseling and psychotherapy: A case approach (4th ed.). Pearson Higher Education, Inc.

Shakiba, S., Mohamadkhani, P., Poorshahbaz, A., & Moshtaghbidokhti, N. (2011). The efficacy of Brief Object Relations Psychotherapy on major depressive disorder comorbid with cluster C personality. Medical Journal of The Islamic Republic of Iran (MJIRI), 25(2), 57-65.

Shedler, J. (2010). The efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 65(2), 98-109.

St. Claire, M. (1996). Object relations and self psychology: An introduction (2nd Edition). Brooks/Cole.

Van, H. L., Hendriksen, M., Schoevers, R. A., Peen, J., Abraham, R. A., & Dekker, J. (2008). Predictive value of object relations for therapeutic alliance and outcome in psychotherapy for depression: An exploratory study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196(9), 655-662.

Wampold, B. E. (2001). The great psychotherapy debate: Model, methods, and findings. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wampold, B. E. & Imel, Z.E. (2015). The great psychotherapy debate. Routledge.

Note: Sources not referenced are indirect quotes from Murdock, 2017.