Secular Reincarnation Fails

Formally, the reasoning may be set out as follows:

Argument: Existence is Not Evidence of Immortality

- Bayesian Principle of Evidence

E supports H iff P(E | H) > P(E | ¬H). - Definitions

Let

a. Hperm: a permissive theory of persons, under which personal identity can recur (a person may live more than once);

b. Hrest: a restrictive theory of persons, under which personal identity is unrepeatable (a person can live at most once);

c. E: “You exist now.” - Huemer’s Claim

P(E | Hperm) > P(E | Hrest). Therefore, by (1), E supports Hperm; your existence now is evidence for reincarnation. - Equivocation Problem

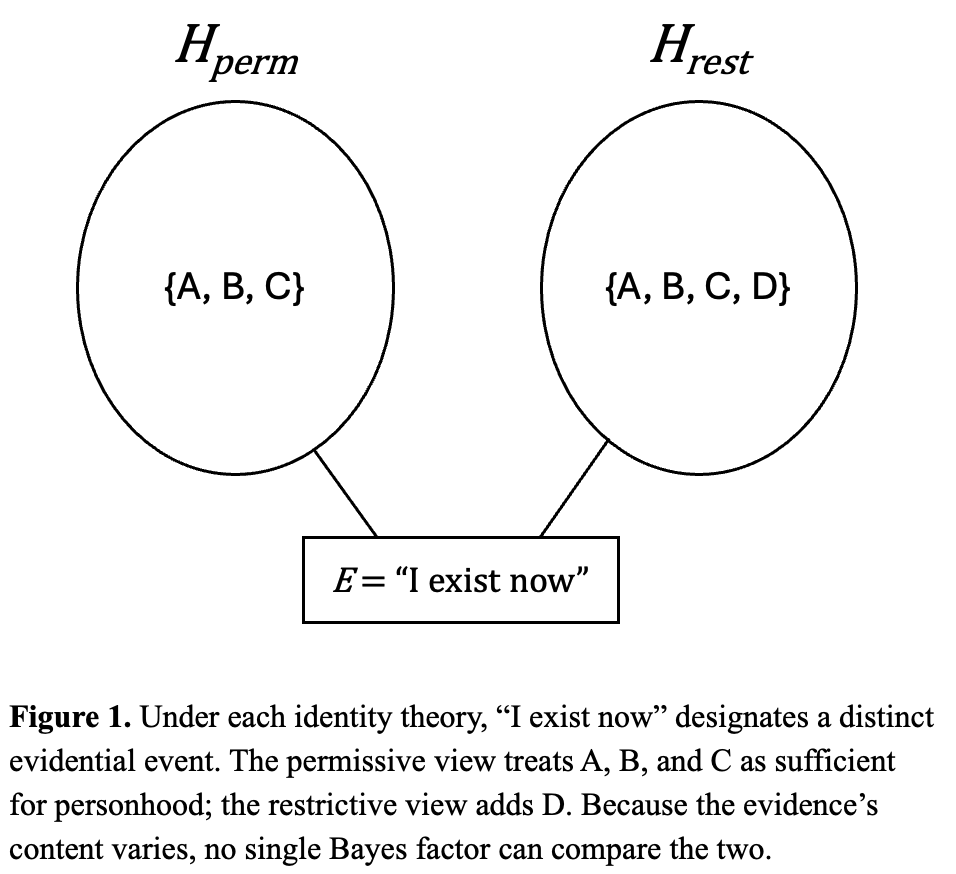

The proposition E does not have the same content under the two hypotheses.

a. Under Hperm: “Someone with A, B, C exists now.”

b. Under Hrest: “Someone with A, B, C, D exists now.”

Hence Eperm ≠ Erest; the evidence proposition shifts meaning. - Bayesian Comparability Condition

For Bayes’ theorem to apply, E must refer to the same proposition across all hypotheses. If E varies in meaning, the probabilities P(E | Hperm) and P(E | Hrest) belong to different reference classes, and their ratio (the Bayes factor) is undefined. - Semantic Repair

To restore comparability, fix a single proposition E*:“A being with A, B, C exists now.”

Under this consistent definition,

P(E* | Hperm) = P(E* | Hrest)eliminating any evidential advantage for Hperm. - Conclusion

Huemer’s argument fails because it equivocates on the evidence term.

Once the proposition “you exist now” is defined consistently across Hperm and Hrest, your existence confers no Bayesian support for reincarnation or personal immortality.

Explanatory Note.

This argument concerns only the evidential relation between present existence and competing theories of personal identity, not the broader metaphysics of mind or survival. The variables A, B, C, and D are schematic placeholders for whatever psychological or physical conditions a theory takes to individuate a person; they carry no empirical commitments of their own. The analysis assumes that introspection or self-locating awareness cannot, by themselves, yield special epistemic access to which theory of persons is correct—or if such a route exists, it has yet to be articulated by defenders of the permissive view. Nothing here precludes the possibility that independent evidence (empirical, metaphysical, or otherwise) might someday support Hperm or a reincarnation hypothesis. The point is only that existence alone cannot do that evidential work.