Hormone Therapy & Suicidality: What The 2025 Follow-Up Study Shows & FAQs.

The Journal of Pediatrics:

Changes in Suicidality Among Transgender Adolescents Following HT: An Extended Study

In 2019, coming out of my dissertation (Allen et al., 2019), my co-authors and I published a small observational study (N = 47) examining changes in well-being and suicidality among transgender and non-binary (TNB) adolescents after the initiation of hormone therapy (HT). Given the replication crisis in the sciences (Ioannidis, 2005; Open Science Collaboration, 2015) and the well-documented decline effect (where initially large effects often shrink or vanish with replication; see also my Blog on Purple Hat Therapies), larger and better-designed replications are necessary before drawing strong conclusions.

This year, we completed a substantially expanded follow-up with 432 youth (links with access to PDF/article), where we revisit our previous research questions with a larger cohort and over a longer observation window. Although many studies in gender care, especially around youth, remain constrained by the practical and logistical limits of ethical clinical research (small samples, short follow-up periods, and the difficulties of conducting randomized controlled trials) accumulating evidence strengthens our confidence when patterns recur across independent datasets.

Our 2025 study, Changes in Suicidality Among Transgender Adolescents Following HT: An Extended Study, confirms the primary findings of the initial 2019 research. The reduction in suicidality following HT remains significant. The estimated effect size decreased from large to medium, which is expected with a larger sample (aligning with broader trends in replication research).

The most salient pattern in the expanded sample was a drop in self-reported suicidality among TNB youth:

| Outcome Metric | Baseline (Start) | Follow-up (End) |

|---|---|---|

| Endorsing Suicidality | 92 (21.3%) | 32 (7.4%) |

| Reported Recent Suicide Attempts | 13 (3.0%) | 2 (0.5%) |

Most patients did not report suicidality to begin with (at baseline), and many are doing well in school, relationships, and everyday life. Among those who did endorse suicidality at baseline, the rate of endorsement dropped by nearly two-thirds (65.2%) at follow-up. Patients endorsing recent suicide attempts dropped by 84.6%. In other words, new suicide attempts were uncommon during the follow-up period, even among those who began HT with a recent attempt. Although observational studies cannot definitively establish causation, seeing similar improvements across multiple samples makes it increasingly likely that the association reflects a real trend worth taking seriously. In fact, no reasonable analytical decision could obscure the finding that rates of suicidality endorsement significantly dropped (Allen et al., 2025b).

This follow-up study matters because evidence in medicine accumulates over time. It would be rare that one study settles any question (though, I am in favor of devoting resources to larger, better studies rather than multiple small studies). Evaluating evidence requires assessing the limitations and quality of individual studies, as well as replication and convergence across methods and populations. Science is inherently iterative and self-correcting (Nosek, 2025). Even studies with acknowledged limitations can still contribute when their results align with broader empirical patterns.

In the area of gender care for TNB youth, the pattern of findings have been notably consistent. Across dozens of studies, transgender youth who begin HT typically experience measurable improvements in a wide range of outcomes (Turban, 2025; Budge et al., 2025). Of course, evidence is not perfect or without limitations, and causal inferences should be made cautiously. Some improvements may also reflect maturation, psychosocial support, expectations of benefit, or broader changes in life circumstances. And some of these positive changes may have only been enabled by HT. Still, the recurring pattern across independent studies suggests that the observed improvements are unlikely to be purely random or idiosyncratic.

But evidence-based medicine has never been only about the data. The evidence alone cannot tell us or a patient what to do. Clinical decisions require incorporating patients and stakeholders’ values and preferences. Different people place different weights on potential benefits and risks, and evidence alone cannot settle some of those value judgments and levels of risk tolerance. Of course, choosing not to do something also is not value neutral or risk free.

As a mental health practitioner, clarity about the role and limits of therapy is important. There are things therapy can and cannot do. There is no credible evidence that therapy can reliably change a person’s gender identity or reduce gender dysphoria by attempting to alter it directly. The aim of (gender) therapy lies elsewhere: to help patients understand themselves, explore their self-expression and what feels right for them, clarify their values, and make informed, values-aligned decisions. This includes supporting patients whether they pursue medical interventions or decide that non-medical approaches or non-treatment are right choice for them.

If we are practicing good gender care, we are never telling any patient “You are transgender and you need X intervention.” It is about supporting the patient as they figure that out themselves (if they don’t already know) and providing accurate information about the full range of treatment options, which may include non-treatment, and ensuring that any decision is grounded in informed consent.

Stepping back, the picture we see across the literature is one of consistent evidence of benefit, albeit based on studies that vary in design and often face significant methodological constraints. The ‘signal’ is not perfect and does not meet strict causal standards (most medical interventions do not). But the findings regarding gender care for youth are stable across time, samples, and research groups, and reflect the best evidence we currently have in a challenging and evolving field of study. That is what research looks like in real world settings and conditions. And ultimately, decisions about care must be made collaboratively by families and knowledgeable clinicians who understand the developmental context, the values and preferences of those involved, the limitations of current evidence, and who adhere to established standards of care.

Study FAQs: Responses to Common Concerns

-

It’s a reasonable question. But it starts from the wrong assumptions.

The study wasn’t trying to isolate hormone therapy (HT) from everything else. It was designed to reflect how care actually works in gender clinics, where HT is delivered within a multidisciplinary model and standards of care (that includes mental-health support).

Therapy isn’t an optional “add-on.” Most youth who need support are already in therapy or are connected to community providers as part of standard care. That means there isn’t enough natural variation to “control for.” Nearly everyone gets some level of support, and the few who don’t differ for reasons unrelated to treatment (access, refusal, family dynamics, etc.). Those differences would mislead any attempt to compare “therapy vs. no therapy.”

It’d be like trying to study whether seatbelts make drivers safer in a group where almost everyone is already wearing one. There just isn’t enough difference to analyze, and the few who aren’t wearing a seatbelt aren’t randomly chosen: they differ in other important ways that matter more than the seatbelt itself.

The study does not answer the question: “What is the isolated effect of hormones alone?”

Instead, we answer: “What happens when young people receive hormone therapy as it is actually delivered in real clinical practice?”That makes the findings ecologically valid. They reflect real-world care, not an artificial experimental setup.

-

It’s true that control groups strengthen causal claims, but for this population, a true control group is practically and ethically impossible to create except in very rare circumstance (Schall, 2025). When researchers actually attempted this for puberty blockers (Mul et al., 2001), every family assigned to the untreated control group withdrew and sought care elsewhere. That outcome reflects the real constraint: families who want care will not remain in a “no-treatment” arm when other avenues exist.

Our study reflects treatment as usual (TAU), not an artificial experimental design in which access is withheld. In practice, a control group only becomes feasible when access to care has been restricted by law or policy and patients cannot obtain treatment elsewhere.

A comparison group would add value. But defining one is not straightforward. What would count as appropriate? Cisgender youth? Youth seeking but denied care? Youth with similar distress from unrelated causes? None are clean matches and some are not obtainable.

Even without a control group, the study provides meaningful, ecologically valid information about real clinical outcomes. The design doesn’t claim causation; it reports how suicidality changed over time in patients actually receiving care with a dataset that is rarely available and difficult to obtain.

-

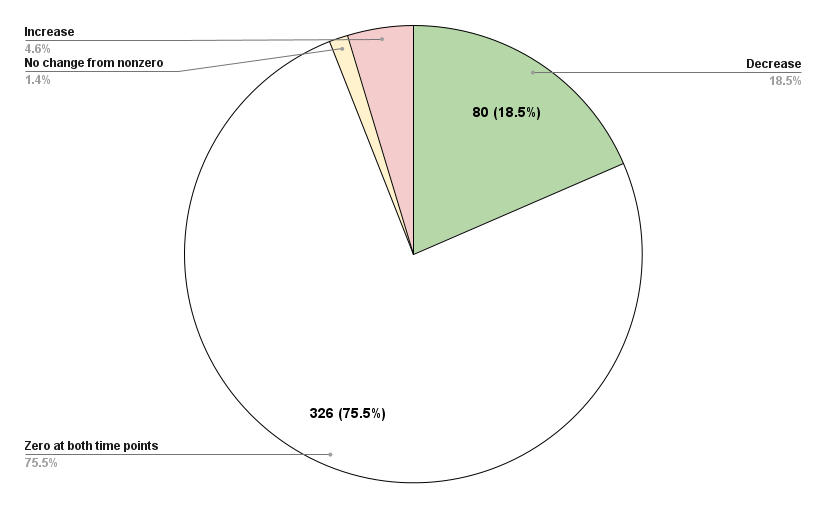

Regression to the mean is always worth considering, but it doesn’t align with what we observed. Regression occurs when people start with extreme values and move toward average over time. But most youth in the study had zero suicidality at baseline and stayed at zero. You can’t regress from 0 to 0.

Among youth who did begin with non-zero suicidality, reductions were:

consistent across multiple years,

in the clinically expected direction, and

replicated with a larger, longer dataset (Allen et al., 2019).

Just as important: we saw no signal of group-level worsening. Some public narratives imply that regret or decline is common after starting HT; our data simply do not show that within the follow-up period.

To contextualize outcomes, our deterioration rate (4.6%) was comparable to or lower than deterioration rates seen in mental-health treatments more broadly (~5% to 10%). That doesn’t prove causation, of course, but it shows the pattern isn’t consistent with simple regression effects or broad decline.

Regression to the mean doesn’t fully explain the results we found.

-

You can read the full exchange here:

Letter to the Editor: The Ask Suicide-Screening Questions “Continuous Score”: An Unvalidated Endpoint

Our Reply: Analytic Treatment of the ASQ: Justification and Robustness of Findings

Both are pieces are technical, so here is a simplified breakdown of what the letter alleged and why those concerns don’t actually undermine the study.

Claim #1: We inappropriately turned the ASQ into a continuous score by summing yes/no items.

Reality: Summing binary items into an ordered severity score is routine in behavioral health research. Examples include:

ACE scores (count of 0/1 exposures)

Symptom-count indices in psychiatry (e.g., number of depressive symptoms present)

Risk screeners that sum yes/no indicators into a total score

The same logic applies to widely used measures like the PHQ-9: each item is ordinal and not evenly spaced, yet the total score is used as an indicator of severity. The purpose is to reflect more or less of the underlying construct: not to claim perfectly equal steps. Our use of the ASQ follows that same well-established approach, just as others have done with the ASQ (e.g., Kaurin et al., 2024).

Claim #2: Summing assumes the ASQ steps (0 → 4) are evenly spaced “units” of suicide risk.

Reality: That assumption appears nowhere in our paper, and our analysis doesn’t require it. The critique is aimed at a claim that was never made. We used the ASQ total for a straightforward: to examine changes in suicidality over time, which is stated plainly in the first three words of the title.

For that purpose, treating the ASQ total as an “ordered measure” is entirely appropriate. Ordered simply means that higher numbers reflect more suicidality; it does not require the steps to be evenly spaced. It’s similar to tracking a shift from “severe → moderate → mild” pain: the categories aren’t equally spaced, but the direction clearly matters.

As part of our analysis, we also checked the standard assumptions for this type of statistical analysis (including linearity), and they were satisfied: meaning the ASQ data behaved the way an our analysis (ANCOVA) requires.

Testing the Critique: Does this change what the data show?

The commentary argues that the ASQ levels (0, 1, 2, 3, 4) aren’t equally spaced. If one wanted to make the scoring “even,” the most conservative approach would be to remove the extreme item (item 4, recent suicide attempt) because it represents the biggest jump in severity. Removing item 4 would “smooth out” the scale.

We did that. And the results were unchanged. In this cohort, new suicide attempts were rare, and reductions in suicidality were common. No statistical critique can undermine this simple descriptive fact.

-

In theory, any retrospective study could miss events that happen entirely outside a health system. But in this setting, silent discontinuation within the observation window is extremely unlikely for several reasons:

Most health-system visits trigger a suicidality screening (not just gender clinic visits). In the hospital system, most routine clinical encounters automatically include a suicidality screening when one hasn’t been filled out recently. So a patient could be seen in nearly any clinic and still be captured in the data. The study did not rely on patients returning only to the gender clinic.

You cannot quietly stop HT without it showing up in the chart. Staying on treatment requires labs, follow-ups, refills, and dose adjustments: if someone stopped, those activities would stop too. Every chart was manually reviewed, and no discontinuation was found beyond the seven documented cases (4 identity shifts while still gender diverse, 2 unknown reasons, & 1 hair-loss concerns).

Every participant already had a follow-up suicidality assessment after starting HT. The study included only youth who had a baseline ASQ, and a second ASQ at least 3 months after starting HT. Even if some youth later disengaged from all care, the study still includes their last documented ASQ screening while they were receiving HT.

The data do not show a hidden pattern of deterioration. At follow-up: a) Suicidality significantly decreased on average, b) 75.5% had zero suicidality at both timepoints, c) only 4.6% worsened, & d) endorsement of recent suicide attempts dropped from 13 at baseline to 2 at follow-up. For a large number of youth to have secretly stopped HT and worsened dramatically without showing up in any system encounters would require a pattern that is not supported anywhere in the data.

Could someone deteriorate after leaving the entire medical system? Yes, just as they could continue to improve afterwards. That uncertainty exists in every retrospective study. But within the actual data, there is no evidence of widespread silent discontinuation or hidden worsening.

Bottom line: Suicidality was lower at the most recent observed visit. The structure of the health system makes silent discontinuation unlikely, and the observed pattern does not support that concern.

-

Because there was no reason. No one was excluded. If a patient received HT and had a follow-up ASQ at least three months later, they were included. There was no selective filtering, no recruitment process, and no study-driven dropout. A “CONSORT”-style flow chart is used when researchers are actively excluding or enrolling participants; that wasn’t part of this design.

The cohort is exactly what readers assume: every patient who received HT and had a follow-up ASQ.

-

Short answer: no.

The ASQ is built into hospital workflow. It is administered at most visits, or at least every 30 days, across departments. This makes missed assessments unlikely. Every patient in the study had a follow-up ASQ; that’s literally why they are appear in the data set. If a patient never completed a follow-up ASQ, they simply were not part of the before-after analysis.

Some might suggests that a patient could have stopped HT before their follow-up ASQ. If that happened, then it is extremely unlikely they would have been on a dose long enough or high enough to experience irreversible effects. And, even in such an imagined case, it would not undermine the findings. Any such hypothetical patients would not have been included in the analytic sample anyway: all patients youth did receive HT, did return for care, and did complete the ASQ again.

Manual chart review confirmed discontinuation was rare (7 of 432 patients). There is no evidence that a large number quietly stopped treatment or somehow bypassed suicidality screening.

Finally, the study replicated earlier findings using a much larger sample and nearly two years of average follow-up. There is no “missing dataset” that would meaningfully alter the observed pattern: after starting HT, suicidality was uncommon and new attempts were rare.

-

Probably not and there is more reason to suspect the opposite (at least for our specific study design).

By the time a patient sees a pediatric endocrinologist, they’ve already gone through psychological, and sometimes medical, evaluations. They’re essentially at the final step before starting hormone therapy. That situation usually brings relief and optimism. When people feel hopeful or expect good news, they tend to under-report distress, not exaggerate it. Think about the last time you were excited or anticipating good news: you probably didn’t focus on your worst feelings. This fits what the data show: most youth scored zero on the ASQ screening at baseline.

The ASQ is also just a routine safety check. It isn’t used to decide who gets treatment. So, there’s little incentive to “perform” distress. The pattern looks much more like deflated reports of distress at the start, not inflated ones. If anything, that makes the improvements seen after treatment even more noteworthy.